"The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon", Edward Burne-Jones (1898)

Ecos del rey Arturo en el siglo XIX

Saturday, January 30, 2016

El último sueño del rey Arturo en Avalon

Edward Burne-Jones trabajó en esta pintura diecisiete años, dejándola definitivamente inacabada con su muerte en 1898. Resulta interesante el grado de identificación que llegó a sentir el artista con la obra. Intuyendo el final de sus días, Burne-Jones se abocó día y noche a su finalización que, infortunadamente, no ocurrió. Se puede leer un interesante artículo al respecto aquí.

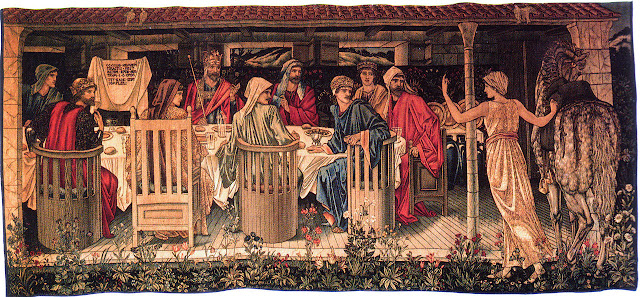

Morris & Co.

Tapetes

Serie de tapetes sobre la búsqueda del Santo Grial que realizó la Morris & Co. en 1890 para el comedor del empresario William Knox D'arcy en Stanmore Hall."Defence of Guenevere, and other poems"

La Defensa de la reina Ginebra,

por William Morris (1858) crédito

THE DEFENCE OF GUENEVERE.

But, knowing now that they would have her speak,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

As though she had had there a shameful blow,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

| 5 |

And feeling it shameful to feel ought but shame

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

She must a little touch it; like one lame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

Still lifted up; and on her cheek of flame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

Still lifted up; and on her cheek of flame

| 10 |

The tears dried quick; she stopped at last and said:

“O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

“O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

"God wot I ought to say, I have done ill,

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

| 15 |

Because you must be right such great lords—still

"Listen, suppose your time were come to die,

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

"The wind was ruffling up the narrow streak

| 20 |

Of river through your broad lands running well:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

"'One of these cloths is heaven, and one is hell,

Now choose one cloth for ever, which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

Now choose one cloth for ever, which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

| 25 |

"'Of your own strength and mightiness; here, see!'

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

[p. 46]

At foot of your familiar bed to see

"A great God's angel standing, with such dyes,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

| 30 |

Held out two ways, light from the inner skies

"Showing him well, and making his commands

Seem to be God's commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

Seem to be God's commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

"And one of these strange choosing cloths was blue,

| 35 |

Wavy and long, and one cut short and red;

No man could tell the better of the two.

No man could tell the better of the two.

"After a shivering half-hour you said,

'God help! heaven's colour, the blue;' and he said, 'hell.'

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

'God help! heaven's colour, the blue;' and he said, 'hell.'

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

| 40 |

"And cry to all good men that loved you well,

'Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;'

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

'Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;'

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

"Like wisest man how all things would be, moan,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

| 45 |

And yet fear much to die for what was sown.

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie."

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie."

Her voice was low at first, being full of tears,

| 50 |

But as it cleared, it grew full loud and shrill,

Growing a windy shriek in all men's ears,

Growing a windy shriek in all men's ears,

A ringing in their startled brains, until

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

| 55 |

Though still she stood right up, and never shrunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

She stood, and seemed to think, and wrung her hair,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

| 60 |

With passionate twisting of her body there:

"It chanced upon a day that Launcelot came

[p. 47]

To dwell at Arthur's court: at Christmas-time

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

"'Son of King Ban of Benwick,' seemed to chime

| 65 |

Along with all the bells that rang that day,

O'er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

O'er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

"Christmas and whitened winter passed away,

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

| 70 |

"And in Summer I grew white with flame,

And bowed my head down—Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

And bowed my head down—Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

"However often Spring might be most thick

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

| 75 |

Careless of most things, let the clock tick, tick,

"To my unhappy pulse, that beat right through

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

"Seemed cold and shallow without any cloud.

| 80 |

Behold my judges, then the cloths were brought:

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

"Belonging to the time ere I was bought

By Arthur's great name and his little love,

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

By Arthur's great name and his little love,

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

| 85 |

"That which I deemed would ever round me move

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

"Stone-cold for ever? Pray you, does the Lord

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

| 90 |

I love God now a little, if this cord

"Were broken, once for all what striving could

Make me love anything in earth or heaven.

So day by day it grew, as if one should

Make me love anything in earth or heaven.

So day by day it grew, as if one should

"Slip slowly down some path worn smooth and even,

| 95 |

Down to a cool sea on a summer day;

[p. 48]

Yet still in slipping there was some small leaven

"Of stretched hands catching small stones by the way,

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

| 100 |

"Back, with the hair like sea-weed; yea all past

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o'ercast

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o'ercast

"In the lone sea, far off from any ships!

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

| 105 |

No minute of that wild day ever slips

"From out my memory; I hear thrushes sing,

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting;

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting;

"I was half mad with beauty on that day,

| 110 |

And went without my ladies all alone,

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

"I was right joyful of that wall of stone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

| 115 |

"Yea right through to my heart, grown very shy

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

"A little thing just then had made me mad;

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

| 120 |

Sometimes, upon my beauty; if I had

"Held out my long hand up against the blue,

And, looking on the tenderly darken'd fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

And, looking on the tenderly darken'd fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

"There, see you, where the soft still light yet lingers,

| 125 |

Round by the edges; what should I have done,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

"And startling green drawn upward by the sun?

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

[p. 49]

| 130 |

"With faintest half-heard breathing sound—why there

I lose my head e'en now in doing this;

But shortly listen—In that garden fair

I lose my head e'en now in doing this;

But shortly listen—In that garden fair

"Came Launcelot walking; this is true, the kiss

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

| 135 |

I scarce dare talk of the remember'd bliss,

"When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

"Never within a yard of my bright sleeves

| 140 |

Had Launcelot come before—and now, so nigh!

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

| 145 |

"Being such a lady could I weep these tears

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn'd this way, straight her conscience sears;

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn'd this way, straight her conscience sears;

"And afterwards she liveth hatefully,

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps,—

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps,—

| 150 |

Gauwaine be friends now, speak me lovingly.

"Do I not see how God's dear pity creeps

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

"Buried in some place far down in the south,

| 155 |

Men are forgetting as I speak to you;

By her head sever'd in that awful drouth

By her head sever'd in that awful drouth

"Of pity that drew Agravaine's fell blow,

I pray your pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

I pray your pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

| 160 |

"Through half your castle-locks! let me not shout

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

"Let not my rusting tears make your sword light!

Ah! God of mercy how he turns away!

Ah! God of mercy how he turns away!

| 165 |

So, ever must I dress me to the fight,

[p. 50]

"So—let God's justice work! Gauwaine, I say,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

"One bitter day in la Fausse Garde, for so

| 170 |

All good knights held it after, saw—

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

"You, Gauwaine, held his word without a flaw,

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed—

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed—

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

| 175 |

"To make a queen say why some spots of red

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say,

'Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say,

'Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

"'Where did you bleed?' and must I stammer out—

Nay, I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

Nay, I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

| 180 |

My sleeve up to my shoulder, where there lay

"'A knife-point last night:' so must I defend

The honour of the lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

The honour of the lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

"This very day, and you were judges here

| 185 |

Instead of God. Did you see Mellyagraunce

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

"Curdled his blood, and how his teeth did dance,

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said,

'Slayer of unarm'd men, here is a chance!

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said,

'Slayer of unarm'd men, here is a chance!

| 190 |

"'Setter of traps, I pray you guard your head,

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

"'For driving weight; hurrah now! draw and do,

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

| 195 |

And I am getting mad with waiting so.'

"He struck his hands together o'er the beast,

Who fell down flat, and grovell'd at his feet,

And groan'd at being slain so young—'at least,'

Who fell down flat, and grovell'd at his feet,

And groan'd at being slain so young—'at least,'

"My knight said, 'Rise you, sir, who are so fleet

[p. 51]

| 200 |

At catching ladies, half-arm’d will I fight,

My left side all uncovered!’ then I weet,

My left side all uncovered!’ then I weet,

“Up sprang Sir Mellyagraunce with great delight

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

| 205 |

“Along the lists look to my stake and pen

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

“The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

“The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

| 210 |

And traversed warily, and ever high

“And fast leapt caitiff’s sword, until my knight

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

“Except a spout of blood on the hot land;

| 215 |

For it was hottest summer; and I know

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand

“And burn, against the heat, would quiver so,

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

| 220 |

“That fell on me. Yet Mellyagraunce was shent,

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

“With all this wickedness; say no rash word

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

| 225 |

Wept all away to grey, may bring some sword

“To drown you in your blood; see my breast rise,

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

“Yea also at my full heart’s strong command,

| 230 |

See through my long throat how the words go up

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

“The shadow likes like wine within a cup

[p. 52]

Of marvellously colour'd gold; yea now

This little wind is rising, look you up,

This little wind is rising, look you up,

| 235 |

"And wonder how the light is falling so

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

"To say this thing is vile? or will you care

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

| 240 |

When you can see my face with no lie there

"For ever? am I not a gracious proof—

'But in your chamber Launcelot was found'—

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

'But in your chamber Launcelot was found'—

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

"When a queen says with gentle queenly sound:

| 245 |

'O true as steel come now and talk with me,

I love to see your step upon the ground

I love to see your step upon the ground

"'Unwavering, also well I love to see

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

| 250 |

"'The thing they seem to mean: good friend, so dear

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

"'If you come not, I fear this time I might

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

| 255 |

When I was young, and green hope was in sight;

"'For no man cares now to know why I sigh;

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

"'So thick in the gardens; therefore one so longs

| 260 |

To see you, Launcelot; that we may be

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

"'Just for one night.' Did he not come to me?

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said 'come?' there was one less than three

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said 'come?' there was one less than three

| 265 |

"In my quiet room that night, and we were gay;

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

"I looked at Launcelot's face and could not speak,

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

| 270 |

Then I remember how I tried to shriek,

[p. 53]

"And could not, but fell down; from tile to tile

The stones they threw up rattled o'er my head,

And made me dizzier; till within a while

The stones they threw up rattled o'er my head,

And made me dizzier; till within a while

"My maids were all about me, and my head

| 275 |

On Launcelot's breast was being soothed away

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said—

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said—

"By God! I will not tell you more to-day,

Judge any way you will—what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

Judge any way you will—what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

| 280 |

"How Launcelot still'd their bawling, the mad fit

That caught up Gauwaine—all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

That caught up Gauwaine—all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happen'd these long years,

Whatever may have happen'd these long years,

| 285 |

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie!

"All I have said is truth, by Christ's dear tears."

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn'd sideways; listening, like a man who hears

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn'd sideways; listening, like a man who hears

His brother's trumpet sounding through the wood

| 290 |

Of his foes' lances. She lean'd eagerly,

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

At last hear something really; joyfully

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

| 295 |

The knight who came was Launcelot at good need

"Queen Guinevere (La Belle Iseult)"

Esta pintura posee la particularidad de ser la única que terminó William Morris. Morris, a pesar de su asociación con la Hermandad Prerrafaelista, nunca confió en su talento para la pintura. Sin embargo, luego adquiriría popularidad como diseñador y artesano al fundar Morris & Co. y sus ideas sobre recuperar la calidad de la manufactura artesanal (tal como se hacía en la Edad Media) inspirarían el movimiento de Arts & Crafts.

El nombre de la pintura relaciona la figura de la reina Ginebra con la de la adúltera Isolda. La modelo de la pintura, Jane Burden, se casaría con Morris un año después de acabada esta. Curiosamente, también la propia Jane, quien permaneció casada con Morris hasta la muerte de este en 1896, mantuvo relaciones extra maritales, en su caso con el poeta Wilfrid Blunt y, posiblemente, con el prerrafaelista Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

"Queen Guinevere (La Belle Iseult)", William Morris (1858)

"Morgan Le Fay"

Morgan Le Fay o Morgana, media hermana del rey Arturo, puede o no actuar como su antagonista dependiendo de la fuente. A pesar de que la versión de Morgana-antagonista ha adquirido mayor popularidad, algunos relatos la colocan como una de las tres mujeres que escoltan al moribundo Arturo hacia la isla de Avalon.

"Morgan Le Fay", Frederick Augustus Sandys (1864)

"The Damsel of the Holy Grail"

Tanto la profusión de rojo en las vestiduras y el cabello como la vid hacen alusión al sacrificio de la Eucaristía. La identificación del Santo Grial con el cáliz que utilizó Cristo en la Última Cena demuestra la paulatina asimilación del cristianismo a la figura del rey Arturo.

"Idylls of the King" (1859-1885)

A pesar de figurar como uno de los poemas más conocidos de Alfred, Lord Tennyson, La Dama de Shalott se inserta en una larga lista de composiciones que realizó este, uno de los grandes poetas victorianos, en torno a la Materia de Bretaña. En "Idylls of the King", Tennyson desarrolla ampliamente el mito artúrico a través de doce poemas narrativos. A lo largo de los años, estos poemas han contribuido en gran medida a ensalzar el espíritu patriótico inglés.

Los poemas se pueden consultar en esta dirección.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)