"The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon", Edward Burne-Jones (1898)

Saturday, January 30, 2016

El último sueño del rey Arturo en Avalon

Edward Burne-Jones trabajó en esta pintura diecisiete años, dejándola definitivamente inacabada con su muerte en 1898. Resulta interesante el grado de identificación que llegó a sentir el artista con la obra. Intuyendo el final de sus días, Burne-Jones se abocó día y noche a su finalización que, infortunadamente, no ocurrió. Se puede leer un interesante artículo al respecto aquí.

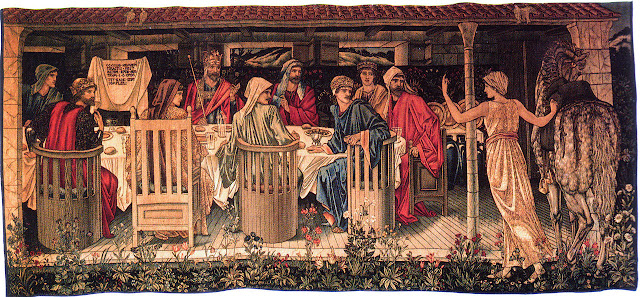

Morris & Co.

Tapetes

Serie de tapetes sobre la búsqueda del Santo Grial que realizó la Morris & Co. en 1890 para el comedor del empresario William Knox D'arcy en Stanmore Hall."Defence of Guenevere, and other poems"

La Defensa de la reina Ginebra,

por William Morris (1858) crédito

THE DEFENCE OF GUENEVERE.

But, knowing now that they would have her speak,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

As though she had had there a shameful blow,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

| 5 |

And feeling it shameful to feel ought but shame

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

She must a little touch it; like one lame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

Still lifted up; and on her cheek of flame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

Still lifted up; and on her cheek of flame

| 10 |

The tears dried quick; she stopped at last and said:

“O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

“O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

"God wot I ought to say, I have done ill,

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

| 15 |

Because you must be right such great lords—still

"Listen, suppose your time were come to die,

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

"The wind was ruffling up the narrow streak

| 20 |

Of river through your broad lands running well:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

"'One of these cloths is heaven, and one is hell,

Now choose one cloth for ever, which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

Now choose one cloth for ever, which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

| 25 |

"'Of your own strength and mightiness; here, see!'

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

[p. 46]

At foot of your familiar bed to see

"A great God's angel standing, with such dyes,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

| 30 |

Held out two ways, light from the inner skies

"Showing him well, and making his commands

Seem to be God's commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

Seem to be God's commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

"And one of these strange choosing cloths was blue,

| 35 |

Wavy and long, and one cut short and red;

No man could tell the better of the two.

No man could tell the better of the two.

"After a shivering half-hour you said,

'God help! heaven's colour, the blue;' and he said, 'hell.'

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

'God help! heaven's colour, the blue;' and he said, 'hell.'

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

| 40 |

"And cry to all good men that loved you well,

'Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;'

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

'Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;'

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

"Like wisest man how all things would be, moan,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

| 45 |

And yet fear much to die for what was sown.

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie."

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie."

Her voice was low at first, being full of tears,

| 50 |

But as it cleared, it grew full loud and shrill,

Growing a windy shriek in all men's ears,

Growing a windy shriek in all men's ears,

A ringing in their startled brains, until

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

| 55 |

Though still she stood right up, and never shrunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

She stood, and seemed to think, and wrung her hair,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

| 60 |

With passionate twisting of her body there:

"It chanced upon a day that Launcelot came

[p. 47]

To dwell at Arthur's court: at Christmas-time

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

"'Son of King Ban of Benwick,' seemed to chime

| 65 |

Along with all the bells that rang that day,

O'er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

O'er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

"Christmas and whitened winter passed away,

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

| 70 |

"And in Summer I grew white with flame,

And bowed my head down—Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

And bowed my head down—Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

"However often Spring might be most thick

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

| 75 |

Careless of most things, let the clock tick, tick,

"To my unhappy pulse, that beat right through

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

"Seemed cold and shallow without any cloud.

| 80 |

Behold my judges, then the cloths were brought:

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

"Belonging to the time ere I was bought

By Arthur's great name and his little love,

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

By Arthur's great name and his little love,

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

| 85 |

"That which I deemed would ever round me move

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

"Stone-cold for ever? Pray you, does the Lord

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

| 90 |

I love God now a little, if this cord

"Were broken, once for all what striving could

Make me love anything in earth or heaven.

So day by day it grew, as if one should

Make me love anything in earth or heaven.

So day by day it grew, as if one should

"Slip slowly down some path worn smooth and even,

| 95 |

Down to a cool sea on a summer day;

[p. 48]

Yet still in slipping there was some small leaven

"Of stretched hands catching small stones by the way,

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

| 100 |

"Back, with the hair like sea-weed; yea all past

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o'ercast

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o'ercast

"In the lone sea, far off from any ships!

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

| 105 |

No minute of that wild day ever slips

"From out my memory; I hear thrushes sing,

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting;

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting;

"I was half mad with beauty on that day,

| 110 |

And went without my ladies all alone,

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

"I was right joyful of that wall of stone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

| 115 |

"Yea right through to my heart, grown very shy

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

"A little thing just then had made me mad;

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

| 120 |

Sometimes, upon my beauty; if I had

"Held out my long hand up against the blue,

And, looking on the tenderly darken'd fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

And, looking on the tenderly darken'd fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

"There, see you, where the soft still light yet lingers,

| 125 |

Round by the edges; what should I have done,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

"And startling green drawn upward by the sun?

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

[p. 49]

| 130 |

"With faintest half-heard breathing sound—why there

I lose my head e'en now in doing this;

But shortly listen—In that garden fair

I lose my head e'en now in doing this;

But shortly listen—In that garden fair

"Came Launcelot walking; this is true, the kiss

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

| 135 |

I scarce dare talk of the remember'd bliss,

"When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

"Never within a yard of my bright sleeves

| 140 |

Had Launcelot come before—and now, so nigh!

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

| 145 |

"Being such a lady could I weep these tears

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn'd this way, straight her conscience sears;

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn'd this way, straight her conscience sears;

"And afterwards she liveth hatefully,

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps,—

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps,—

| 150 |

Gauwaine be friends now, speak me lovingly.

"Do I not see how God's dear pity creeps

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

"Buried in some place far down in the south,

| 155 |

Men are forgetting as I speak to you;

By her head sever'd in that awful drouth

By her head sever'd in that awful drouth

"Of pity that drew Agravaine's fell blow,

I pray your pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

I pray your pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

| 160 |

"Through half your castle-locks! let me not shout

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

"Let not my rusting tears make your sword light!

Ah! God of mercy how he turns away!

Ah! God of mercy how he turns away!

| 165 |

So, ever must I dress me to the fight,

[p. 50]

"So—let God's justice work! Gauwaine, I say,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

"One bitter day in la Fausse Garde, for so

| 170 |

All good knights held it after, saw—

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

"You, Gauwaine, held his word without a flaw,

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed—

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed—

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

| 175 |

"To make a queen say why some spots of red

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say,

'Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say,

'Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

"'Where did you bleed?' and must I stammer out—

Nay, I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

Nay, I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

| 180 |

My sleeve up to my shoulder, where there lay

"'A knife-point last night:' so must I defend

The honour of the lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

The honour of the lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

"This very day, and you were judges here

| 185 |

Instead of God. Did you see Mellyagraunce

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

"Curdled his blood, and how his teeth did dance,

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said,

'Slayer of unarm'd men, here is a chance!

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said,

'Slayer of unarm'd men, here is a chance!

| 190 |

"'Setter of traps, I pray you guard your head,

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

"'For driving weight; hurrah now! draw and do,

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

| 195 |

And I am getting mad with waiting so.'

"He struck his hands together o'er the beast,

Who fell down flat, and grovell'd at his feet,

And groan'd at being slain so young—'at least,'

Who fell down flat, and grovell'd at his feet,

And groan'd at being slain so young—'at least,'

"My knight said, 'Rise you, sir, who are so fleet

[p. 51]

| 200 |

At catching ladies, half-arm’d will I fight,

My left side all uncovered!’ then I weet,

My left side all uncovered!’ then I weet,

“Up sprang Sir Mellyagraunce with great delight

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

| 205 |

“Along the lists look to my stake and pen

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

“The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

“The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

| 210 |

And traversed warily, and ever high

“And fast leapt caitiff’s sword, until my knight

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

“Except a spout of blood on the hot land;

| 215 |

For it was hottest summer; and I know

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand

“And burn, against the heat, would quiver so,

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

| 220 |

“That fell on me. Yet Mellyagraunce was shent,

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

“With all this wickedness; say no rash word

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

| 225 |

Wept all away to grey, may bring some sword

“To drown you in your blood; see my breast rise,

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

“Yea also at my full heart’s strong command,

| 230 |

See through my long throat how the words go up

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

“The shadow likes like wine within a cup

[p. 52]

Of marvellously colour'd gold; yea now

This little wind is rising, look you up,

This little wind is rising, look you up,

| 235 |

"And wonder how the light is falling so

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

"To say this thing is vile? or will you care

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

| 240 |

When you can see my face with no lie there

"For ever? am I not a gracious proof—

'But in your chamber Launcelot was found'—

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

'But in your chamber Launcelot was found'—

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

"When a queen says with gentle queenly sound:

| 245 |

'O true as steel come now and talk with me,

I love to see your step upon the ground

I love to see your step upon the ground

"'Unwavering, also well I love to see

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

| 250 |

"'The thing they seem to mean: good friend, so dear

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

"'If you come not, I fear this time I might

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

| 255 |

When I was young, and green hope was in sight;

"'For no man cares now to know why I sigh;

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

"'So thick in the gardens; therefore one so longs

| 260 |

To see you, Launcelot; that we may be

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

"'Just for one night.' Did he not come to me?

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said 'come?' there was one less than three

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said 'come?' there was one less than three

| 265 |

"In my quiet room that night, and we were gay;

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

"I looked at Launcelot's face and could not speak,

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

| 270 |

Then I remember how I tried to shriek,

[p. 53]

"And could not, but fell down; from tile to tile

The stones they threw up rattled o'er my head,

And made me dizzier; till within a while

The stones they threw up rattled o'er my head,

And made me dizzier; till within a while

"My maids were all about me, and my head

| 275 |

On Launcelot's breast was being soothed away

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said—

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said—

"By God! I will not tell you more to-day,

Judge any way you will—what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

Judge any way you will—what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

| 280 |

"How Launcelot still'd their bawling, the mad fit

That caught up Gauwaine—all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

That caught up Gauwaine—all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

"Nevertheless you, O Sir Gauwaine, lie,

Whatever may have happen'd these long years,

Whatever may have happen'd these long years,

| 285 |

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie!

"All I have said is truth, by Christ's dear tears."

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn'd sideways; listening, like a man who hears

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn'd sideways; listening, like a man who hears

His brother's trumpet sounding through the wood

| 290 |

Of his foes' lances. She lean'd eagerly,

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

At last hear something really; joyfully

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

| 295 |

The knight who came was Launcelot at good need

"Queen Guinevere (La Belle Iseult)"

Esta pintura posee la particularidad de ser la única que terminó William Morris. Morris, a pesar de su asociación con la Hermandad Prerrafaelista, nunca confió en su talento para la pintura. Sin embargo, luego adquiriría popularidad como diseñador y artesano al fundar Morris & Co. y sus ideas sobre recuperar la calidad de la manufactura artesanal (tal como se hacía en la Edad Media) inspirarían el movimiento de Arts & Crafts.

El nombre de la pintura relaciona la figura de la reina Ginebra con la de la adúltera Isolda. La modelo de la pintura, Jane Burden, se casaría con Morris un año después de acabada esta. Curiosamente, también la propia Jane, quien permaneció casada con Morris hasta la muerte de este en 1896, mantuvo relaciones extra maritales, en su caso con el poeta Wilfrid Blunt y, posiblemente, con el prerrafaelista Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

"Queen Guinevere (La Belle Iseult)", William Morris (1858)

"Morgan Le Fay"

Morgan Le Fay o Morgana, media hermana del rey Arturo, puede o no actuar como su antagonista dependiendo de la fuente. A pesar de que la versión de Morgana-antagonista ha adquirido mayor popularidad, algunos relatos la colocan como una de las tres mujeres que escoltan al moribundo Arturo hacia la isla de Avalon.

"Morgan Le Fay", Frederick Augustus Sandys (1864)

"The Damsel of the Holy Grail"

Tanto la profusión de rojo en las vestiduras y el cabello como la vid hacen alusión al sacrificio de la Eucaristía. La identificación del Santo Grial con el cáliz que utilizó Cristo en la Última Cena demuestra la paulatina asimilación del cristianismo a la figura del rey Arturo.

"Idylls of the King" (1859-1885)

A pesar de figurar como uno de los poemas más conocidos de Alfred, Lord Tennyson, La Dama de Shalott se inserta en una larga lista de composiciones que realizó este, uno de los grandes poetas victorianos, en torno a la Materia de Bretaña. En "Idylls of the King", Tennyson desarrolla ampliamente el mito artúrico a través de doce poemas narrativos. A lo largo de los años, estos poemas han contribuido en gran medida a ensalzar el espíritu patriótico inglés.

Los poemas se pueden consultar en esta dirección.

"The Beguiling of Merlin"

Este cuadro fue pintado por el prerrafaelista Edward Burne-Jones. En él retrata una escena donde Nimue, una de las tantas denominaciones de la Dama de Lago (famosa por haber criado a Sir Lancelot y por haber dotado al rey Arturo de la legendaria espada Excalibur), tras haber seducido a Merlín so pretexto de obtener los secretos de sus poderes mágicos, lee su libro de hechizos. La Dama con el tiempo se volvió más poderosa que su maestro y ellos contribuyó con la decadencia del reinado de Arturo. (crédito)

"The Beguiling of Merlin", Edward Burne-Jones (1872-1877)

Ilustraciones de "Idylls of the King" por Gustave Doré

Ilustraciones que realizó el afamado artista Gustave Dore (1832-1883) para acompañar a los poemas de Lord Tennyson en la edición del año 1875.

Thursday, January 7, 2016

"The Egyptian Maid or The Romance of the Water-Lily"

Este poema narra la historia de la doncella egipcia, la cual será desposada por Sir Galahad al final del mismo.

The Egyptian Maid or The Romance of the Water-Lily

por William Wordsworth (1835) crédito

While Merlin paced the Cornish sands,

Forth-looking toward the Rocks of Scilly,

The pleased Enchanter was aware

Of a bright Ship that seemed to hang in air,

Yet was she work of mortal hands,

And took from men her name – THE WATER LILY.

Soft was the wind, that landward blew;

And, as the Moon, o'er some dark hill ascendant,

Grows from a little edge of light

To a full orb, this Pinnace bright,

As nearer to the Coast she drew,

Appeared more glorious, with spread sail and pendant.

Upon this winged Shape so fair

Sage Merlin gazed with admiration:

Her lineaments, thought he, surpass

Aught that was ever shown in magic glass;

In patience built with subtle care;

Or, at a touch, set forth with wondrous transformation.

Now, though a Mechanist, whose skill

Shames the degenerate grasp of modern science,

Grave Merlin (and belike the more

For practising occult and perilous lore)

Was subject to a freakish will

That sapped good thoughts, or scared them with defiance.

Provoked to envious spleen, he cast

An altered look upon the advancing Stranger

Whom he had hailed with joy, and cried,

"My Art shall help to tame her pride – "

Anon the breeze became a blast,

And the waves rose, and sky portended danger.

With thrilling word, and potent sign

Traced on the beach, his work the Sorcerer urges;

The clouds in blacker clouds are lost,

Like spiteful Fiends that vanish, crossed

By Fiends of aspect more malign;

And the winds roused the Deep with fiercer scourges.

But worthy of the name she bore

Was this Sea-flower, this buoyant Galley;

Supreme in loveliness and grace

Of motion, whether in the embrace

Of trusty anchorage, or scudding o'er

The main flood roughened into hill and valley.

Behold, how wantonly she laves

Her sides, the Wizard's craft confounding;

Like something out of Ocean sprung

To be for ever fresh and young,

Breasts the sea-flashes, and huge waves

Top-gallant high, rebounding and rebounding!

But Ocean under magic heaves,

And cannot spare the Thing he cherished:

Ah! what avails that She was fair,

Luminous, blithe, and debonair?

The storm has stripped her of her leaves;

The Lily floats no longer! – She hath perished.

Grieve for her, – She deserves no less;

So like, yet so unlike, a living Creature!

No heart had she, no busy brain;

Though loved, she could not love again;

Though pitied, feel her own distress;

Nor aught that troubles us, the fools of Nature.

Yet is there cause for gushing tears;

So richly was this Galley laden;

A fairer than Herself she bore,

And, in her struggles, cast ashore;

A lovely One, who nothing hears

Of wind or wave – a meek and guileless Maiden.

Into a cave had Merlin fled

From mischief, caused by spells himself had muttered;

And, while repentant all too late,

In moody posture there he sate,

He heard a voice, and saw, with half-raised head,

A Visitant by whom these words were uttered:

"On Christian service this frail Bark

Sailed" (hear me, Merlin!) "under high protection,

Though on her prow a sign of heathen power

Was carved – a Goddess with a Lily flower,

The old Egyptian's emblematic mark

Of joy immortal and of pure affection.

"Her course was for the British strand,

Her freight it was a Damsel peerless;

God reigns above, and Spirits strong

May gather to avenge this wrong

Done to the Princess, and her Land

Which she in duty left, though sad not cheerless.

"And to Caerleon's loftiest tower

Soon will the Knights of Arthur's Table

A cry of lamentation send;

And all will weep who there attend,

To grace that Stranger's bridal hour,

For whom the sea was made unnavigable.

"Shame! should a Child of Royal Line

Die through the blindness of thy malice:"

Thus to the Necromancer spake

Nina, the Lady of the Lake,

A gentle Sorceress, and benign,

Who ne'er embittered any good man's chalice.

"What boots," continued she, "to mourn?

To expiate thy sin endeavour!

From the bleak isle where she is laid,

Fetched by our art, the Egyptian Maid

May yet to Arthur's court be borne

Cold as she is, ere life be fled for ever.

"My pearly Boat, a shining Light,

That brought me down that sunless river,

Will bear me on from wave to wave,

And back with her to this sea-cave;

Then Merlin! for a rapid flight

Through air to thee my charge will I deliver.

"The very swiftest of thy Cars

Must, when my part is done, be ready;

Meanwhile, for further guidance, look

Into thy own prophetic book;

And, if that fail, consult the Stars

To learn thy course; farewell! be prompt and steady."

This scarcely spoken, she again

Was seated in her gleaming Shallop,

That, o'er the yet-distempered Deep,

Pursued its way with bird-like sweep,

Or like a steed, without a rein,

Urged o'er the wilderness in sportive gallop.

Soon did the gentle Nina reach

That Isle without a house or haven;

Landing, she found not what she sought,

Nor saw of wreck or ruin aught

But a carved Lotus cast upon the shore

By the fierce waves, a flower in marble graven.

Sad relique, but how fair the while!

For gently each from each retreating

With backward curve, the leaves revealed

The bosom half, and half concealed,

Of a Divinity, that seemed to smile

On Nina as she passed, with hopeful greeting.

No quest was hers of vague desire,

Of tortured hope and purpose shaken;

Following the margin of a bay,

She spied the lonely Cast-away,

Unmarred, unstripped of her attire,

But with closed eyes, – of breath and bloom forsaken.

Then Nina, stooping down, embraced,

With tenderness and mild emotion,

The Damsel, in that trance embound;

And, while she raised her from the ground,

And in the pearly shallop placed,

Sleep fell upon the air, and stilled the ocean.

The turmoil hushed, celestial springs

Of music opened, and there came a blending

Of fragrance, underived from earth,

With gleams that owed not to the Sun their birth,

And that soft rustling of invisible wings

Which Angels make, on works of love descending.

And Nina heard a sweeter voice

Than if the Goddess of the Flower had spoken:

"Thou hast achieved, fair Dame! what none

Less pure in spirit could have done;

Go, in thy enterprise rejoice!

Air, earth, sea, sky, and heaven, success betoken."

So cheered she left that Island bleak,

A bare rock of the Scilly cluster;

And, as they traversed the smooth brine,

The self-illumined Brigantine

Shed, on the Slumberer's cold wan cheek

And pallid brow, a melancholy lustre.

Fleet was their course, and when they came

To the dim cavern, whence the river

Issued into the salt-sea flood,

Merlin, as fixed in thought he stood,

Was thus accosted by the Dame:

"Behold to thee my Charge I now deliver!

"But where attends thy chariot – where?"

Quoth Merlin, "Even as I was bidden,

So have I done; as trusty as thy barge

My vehicle shall prove – O precious Charge!

If this be sleep, how soft! if death, how fair!

Much have my books disclosed, but the end is hidden."

He spake, and gliding into view

Forth from the grotto's dimmest chamber

Came two mute Swans, whose plumes of dusky white

Changed, as the pair approached the light,

Drawing an ebon car, their hue

(Like clouds of sunset) into lucid amber.

Once more did gentle Nina lift

The Princess, passive to all changes:

The car received her; then up-went

Into the ethereal element

The Birds with progress smooth and swift

As thought, when through bright regions memory ranges.

Sage Merlin, at the Slumberer's side,

Instructs the Swans their way to measure;

And soon Caerleon's towers appeared,

And notes of minstrelsy were heard

From rich pavilions spreading wide,

For some high day of long-expected pleasure.

Awe-stricken stood both Knights and Dames

Ere on firm ground the car alighted;

Eftsoons astonishment was past,

For in that face they saw the last

Last lingering look of clay, that tames

All pride, by which all happiness is blighted.

Said Merlin, "Mighty King, fair Lords,

Away with feast and tilt and tourney!

Ye saw, throughout this Royal House,

Ye heard, a rocking marvellous

Of turrets, and a clash of swords

Self-shaken, as I closed my airy journey.

"Lo! by a destiny well known

To mortals, joy is turned to sorrow;

This is the wished-for Bride, the Maid

Of Egypt, from a rock conveyed

Where she by shipwreck had been thrown;

Ill sight! but grief may vanish ere the morrow."

"Though vast thy power, thy words are weak,"

Exclaimed the King, "a mockery hateful;

Dutiful Child! her lot how hard!

Is this her piety's reward?

Those watery locks, that bloodless cheek!

O winds without remorse! O shore ungrateful!

"Rich robes are fretted by the moth;

Towers, temples, fall by stroke of thunder;

Will that, or deeper thoughts, abate

A Father's sorrow for her fate?

He will repent him of his troth;

His brain will burn, his stout heart split asunder.

"Alas! and I have caused this woe;

For, when my prowess from invading Neighbours

Had freed his Realm, he plighted word

That he would turn to Christ our Lord,

And his dear Daughter on a Knight bestow

Whom I should choose for love and matchless labours.

"Her birth was heathen, but a fence

Of holy Angels round her hovered;

A Lady added to my court

So fair, of such divine report

And worship, seemed a recompence

For fifty kingdoms by my sword recovered.

"Ask not for whom, O champions true!

She was reserved by me her life's betrayer;

She who was meant to be a bride

Is now a corse; then put aside

Vain thoughts, and speed ye, with observance due

Of Christian rites, in Christian ground to lay her."

"The tomb," said Merlin, "may not close

Upon her yet, earth hide her beauty;

Not froward to thy sovereign will

Esteem me, Liege! if I, whose skill

Wafted her hither, interpose

To check this pious haste of erring duty.

"My books command me to lay bare

The secret thou art bent on keeping;

Here must a high attest be given,

What Bridegroom was for her ordained by Heaven;

And in my glass significants there are

Of things that may to gladness turn this weeping.

"For this, approaching, One by One,

Thy Knights must touch the cold hand of the Virgin;

So, for the favoured One, the Flower may bloom

Once more; but, if unchangeagble her doom,

If life departed be for ever gone,

Some blest assurance, from this cloud emerging,

May teach him to bewail his loss;

Not with a grief that, like a vapour, rises

And melts; but grief devout that shall endure

And a perpetual growth secure

Of purposes which no false thought shall cross

A harvest of high hopes and noble enterprises."

"So be it," said the King; – "anon,

Here, where the Princess lies, begin the trial;

Knights each in order as ye stand

Step forth." – To touch the pallid hand

Sir Agravaine advanced; no sign he won

From Heaven or Earth; – Sir Kaye had like denial.

Abashed, Sir Dinas turned away;

Even for Sir Percival was no disclosure;

Though he, devoutest of all Champions, ere

He reached that ebon car, the bier

Whereon diffused like snow the Damsel lay,

Full thrice had crossed himself in meek composure.

Imagine (but ye Saints! who can?)

How in still air the balance trembled;

The wishes, peradventure the despites

That overcame some not ungenerous Knights;

And all the thoughts that lengthened out a span

Of time to Lords and Ladies thus assembled.

What patient confidence was here!

And there how many bosoms panted!

While drawing toward the Car Sir Gawaine, mailed

For tournament, his Beaver vailed,

And softly touched; but, to his princely cheer

And high expectancy, no sign was granted.

Next, disencumbered of his harp,

Sir Tristram, dear to thousands as a brother,

Came to the proof, nor grieved that there ensued

No change; – the fair Izonda he had wooed

With love too true, a love with pangs too sharp,

From hope too distant, not to dread another.

Not so Sir Launcelot; – from Heaven's grace

A sign he craved, tired slave of vain contrition;

The royal Guinever looked passing glad

When his touch failed. – Next came Sir Galahad;

He paused, and stood entranced by that still face

Whose features he had seen in noontide vision.

For late, as near a murmuring stream

He rested 'mid an arbour green and shady,

Nina, the good Enchantress, shed

A light around his mossy bed;

And, at her call, a waking dream

Prefigured to his sense the Egyptian Lady.

Now, while the bright-haired front he bowed,

And stood, far-kenned by mantle furred with ermine,

As o'er the insensate Body hung

The enrapt, the beautiful, the young,

Belief sank deep into the crowd

That he the solemn issue would determine.

Nor deem it strange; the Youth had worn

That very mantle on a day of glory,

The day when he achieved that matchless feat,

The marvel of the PERILOUS SEAT,

Which whosoe'er approached of strength was shorn,

Though King or Knight the most renowned in story.

He touched with hesitating hand,

And lo! those Birds, far-famed through Love's dominions,

The Swans, in triumph clap their wings;

And their necks play, involved in rings,

Like sinless snakes in Eden's happy land; –

"Mine is she," cried the Knight; – again they clapped their pinions.

"Mine was she – mine she is, though dead,

And to her name my soul shall cleave in sorrow;"

Whereat, a tender twilight streak

Of colour dawned upon the Damsel's cheek;

And her lips, quickening with uncertain red,

Seemed from each other a faint warmth to borrow.

Deep was the awe, the rapture high,

Of love emboldened, hope with dread entwining,

When, to the mouth, relenting Death

Allowed a soft and flower-like breath,

Precursor to a timid sigh,

To lifted eyelids, and a doubtful shining.

In silence did King Arthur gaze

Upon the signs that pass away or tarry;

In silence watched the gentle strife

Of Nature leading back to life;

Then eased his Soul at length by praise

Of God, and Heaven's pure Queen – the blissful Mary.

Then said he, "Take her to thy heart

Sir Galahad! a treasure that God giveth

Bound by indissoluble ties to thee

Through mortal change and immortality;

Be happy and unenvied, thou who art

A goodly Knight that hath no Peer that liveth!"

Not long the Nuptials were delayed;

And sage tradition still rehearses

The pomp the glory of that hour

When toward the Altar from her bower

King Arthur led the Egyptian Maid,

And Angels carolled these far-echoed verses; –

Who shrinks not from alliance

Of evil with good Powers,

To God proclaims defiance,

And mocks whom he adores.

A Ship to Christ devoted

From the Land of Nile did go;

Alas! the bright Ship floated,

An Idol at her Prow.

By magic domination

The Heaven-permitted vent

Of purblind mortal passion,

Was wrought her punishment.

The Flower, the Form within it,

What served they in her need?

Her port she could not win it,

Nor from mishap be freed.

The tempest overcame her,

And she was seen no more;

But gently gently blame her,

She cast a Pearl ashore.

The Maid to Jesu hearkened,

And kept to him her faith,

Till sense in death was darkened,

Or sleep akin to death.

But Angels round her pillow

Kept watch, a viewless band;

And, billow favouring billow,

She reached the destined strand.

Blest Pair! whate'er befall you,

Your faith in Him approve

Who from frail earth can call you,

To bowers of endless love!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)